Any creative worth some heft of salt knows that when a work is completed the journey is only half done. The work must cease its building phase—the artist must stop dabbing, the writer must stop fiddling, the dancer must end practice and get on with the stage—and the work must then be passed into the arms of the waiting crowd. The creative must relinquish control; it is a sacrificial act as much as it is a power grab, and the creative must contain this dichotomy if the creating is to continue and not stagnate. Any creative that falls into either of these two holes will lose the friction needed to make and originate new work.

The conversation will start immediately. If the work has impact (for good or for ill) it will be shared and elaborated upon again and again and again, sometimes for weeks, sometimes for years, sometimes for centuries. The creative arc will only end when the masses lower it back into silence. If the work has managed to maintain itself in the physical world, there can be a rebirth. Certain unfortunate works may become perverted, and misused, proceeding forward into the future zombie-like; the creative takes risk every time a work is released and set flown.

Art is the echo of humans in time. The world is full of footprints of us. A book is no lifeless lump of paper, a portrait no mere lonely, empty vessel, but the echoing voice of some individual, who took their two hands and starting clapping fervently into the darkness.

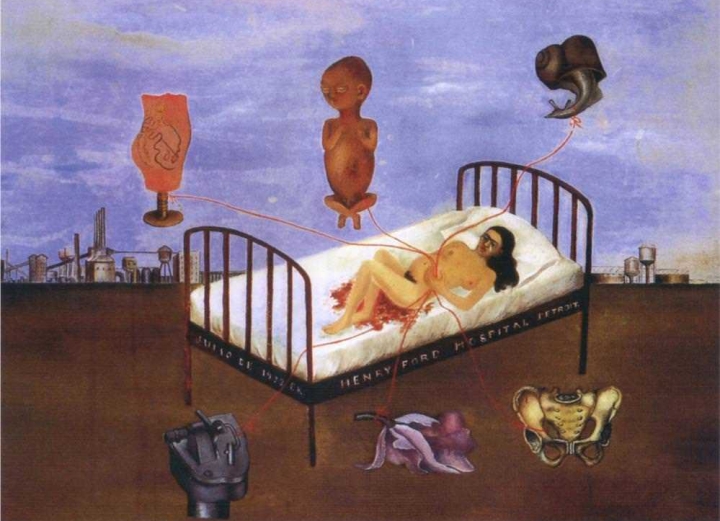

Francine Sterle’s stellar chapbook, Nude in Winter, is a fluent culmination of such echoes, Sterle specifically choosing to reconstruct the voice of paint and painter (sometimes photo and photographer) into the voice of pen and poet. Containing 58 ekphrastic poems, Nude in Winter is both reflection and progression, as image is spun into idea and color into sensation. In each work mulled over, Sterle finds the doorknob, and swings open the closed frames to lay bare the vast landscapes behind them. Interacting with the artworks of known names such as Frida Kahlo, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and William Blake, to the lesser known names of Kiki Smith, Helen Frankenthaler, and Clyfford Still, Sterle’s poems are alive and breathing, speaking in clear voices, while still maintaining the thin string tied to the artist’s liminal, braced world.

I do not know why I come to the window— / white curtains framed by a white wall. / The first breath of morning moves them. / They do not hesitate. / If rain dampens the leaden sill, / they shiver in the washed air, / waver when an animal heat crawls / hour by hour across the yard, / tremble when another summer / crumbles to dust. Some days / they refuse to move as if they hear / crows scolding them from the trees. / Soft as an owl’s downy breast, they allow / the light of dawn into the house / to nest on the floor by the bed. / Behind them, everything fades. / I do not know why I come to the window.

It’s not very often a poetry book sends me whirling through WikiArt.org like a madwoman. Every page turned left my mind pivoting in the wonder: What is she seeing? Where are her eyes? Some art I knew, of course; Giovanni’s Madonna in Prayer and Blake’s Albion Rose are hard not to know. Some artists are so renown, even if the painting itself alludes, the unique style of the elite artist pushes in like a tide, and Monet’s delicate brush, Kahlo’s dreamlike, surrealist spectacles leak in.

And the work can grip you—suddenly. Sterle’s words profess a deep yawning into the body of another. I took it upon myself to read aloud to one of my friends “Rag in Window”, and as the last lines came out I fell into a total sob, bending myself over in the chair, forehead to my thighs and book clutched to my chest, weeping.

Sterle’s work instigated the age old question in me: What is art for? It has often seemed a stupidly worded question for it has seemingly unlimited answers which begs (what I’ve always felt, the more apt question) why ask it at all? Open ended, and circular, I avoid it like the plague, yet always someone’s words, someone’s art, someone’s performance drags me back, drags me back and away and back again, an ebb and flow of life that can’t be discarded, leaving it to become one of the most undying questions of life. Why art? What is art for? What is the artist’s goal? Desired achievement and does it matter? Is the artist a mere secondary element to the grander life of a work, or is it more like the relationship between parent and child? (The endearing mark of its nurture almost inseparable from its identity.)

Nude in Winter pokes at these questions, and so blows them open, where Sterle herself then walks into them like rain. With the falling drops, she finds the shapes, the contours, the materials, and she takes these elements and builds her own art: A departed father, an unspoken love, a prodigal son, a girl sexually abused, the metacognition of a sculpture, the doubts of a old man, the morality of observation, the poet debating words at a desk.

Perhaps this is what art is for: Validation of ourselves. Our inner existence revealed, in the careless cascade of peaches from a basket, the green skin of a bearded violinist grown from the pulled sound, color as emotion and memory, our personal pain expressed vividly in some stranger’s rendering… Is this what art’s for? Sterle asks, rising the question up, and the page turns and it falls back in. Her scapes are visceral, her sight imaginative. The laws of interpretation are bent back around and fed to the reader, revealing the age old question yet again, but in new words: Are there laws? What is art for?

Francine Sterle’s chapbook is worth reading. No blunt halfhearted wisdoms are shoved in your face, no chintzy metaphors and tired facsimiles that often weigh down modern day pop-poetry are present. Sterle’s work invites one into a gallery of gasping, singing, whispering beings, each poem displaying another arc, each line carved alive from out the canvas. It is a beautiful book, an intimate book. A book worth reading and a book worth having on your shelf.

Five out of five stars for Francine Sterle’s Nude in Winter.

The featured image is Peaches by the founder of French impressionism, Claude Monet. (1883) Available via the public domain. All the artworks (with the exception of Kahlo’s Henry Ford Hospital) are featured in Francine Sterle’s ekphrastic chapbook, Nude in Winter.

Interesting post 🙂

LikeLike

Glad it piqued your interest! Thanks kindly.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I always love reading your prose!

LikeLike

Thanks, Sam!

LikeLike