From 2012 to early 2018, I lived in a one bedroom apartment on the edge of a cemetery, and my life was full of crows.

Out my window, just beyond my balcony, in the Seattle fog that rolls in during the late and early year, the trees would hang as ghostly elementals over the stones, the graves shone slick with morning dew, and all along the roads there would be dozens and dozens of sleek black crows. Crows refined looking, and crows ruffly and cowled, crows young and crows old. I’d walk through the cemetery, and they’d line the branches, both eyeing and disregarding me. Somedays they’d set themselves to a chorus, but mostly they’d give small caw here and there. One time, I spotted a beautiful feather, and picked it up; all together, they began to scold me, and insisted that I drop the feather and leave the premises at once. We made up, and went on with our mutual ignoring; neither of us really too interested in the other, but we were neighbors, so we behaved neighborly.

I’ve never been terribly in love with crows, but from time-to-time I have admired them from afar. It is hard for me to love animals in much the way the modern world does, what with the abundant cooing and fawning over their fluffy bodies and lovely eyes. Mine has always been too encased in respect to allow so much coddling. I’ve always viewed animals, both domestic and wild, in much the same way I view people: individuals who deserve their due space and freedom. However, to say I imagine animals as same to people, would duly be a mistake. Nature has its paths, and at some point humanity deviated and forged its own. This is not a tragedy, nor an ascendance; the animals have their lives, and we have ours. Each of us holds some power over the other, and each of us applies to the will of the Earth. We different, yet equal things.

But I do prefer to be outside than in, and I do prefer a book about wilderness and ecosystems over a book about mechanisms and molecularism. It is the whole, in tandem with itself, that I find most interesting. That which exists not alongside, but entangled with. So naturalism attracts me, with its many threads and knots and bows. When I spotted Crow Planet: Essential Wisdom from the Urban Wilderness at a local bookstore, I was instantly intrigued. Words “urban” and “wilderness” are not typically harmoniously found together, and as this segregationist idea of what constitutes Nature (capital N) has always nagged me, I thought I’d give it a whirl. That its author Lyanda Lynn Haupt lives in Seattle was an added bonus. A whole book about my crow neighbors—irresistible.

Within the first ten pages, I learned new things about crows. This was an encouraging start, and that encouragement turned into satisfaction throughout the reading. Finely worded, with silky prose and verse that at times teetered on the demurely, Crow Planet takes the cloak of a memoir, Lyanda Haupt draping every page in the details of her daily life and in the emotion of her inner being. Openly discussing her bouts of depression, her motherhood, her interactions with people, her work with the Audubon Society and her own personal pursuits both studious and spiritual, Haupt pens us a braid of narratives, each ribbon of discussion carefully folded in with the others, again and again, intersecting things into a diligent plait. Haupt takes us across and down all sorts of avenues: from the grooming techniques of birds to Greek philosophers, from the stringent teaching styles of Louis Agassiz to the simple enlightenments of taking a walk, Haupt makes it clear that things intertwine.

Clearly, our cities, suburbs, and houses cry out for improvements that reflect ecological knowledge. I am not claiming they are as natural as those places we traditionally think of as Nature or Wilderness. They are not enough. They are, nevertheless, inhabited by spiders, snails, raccoons, hawks, coyotes, earthworms, fungi, snakes, and crows. They are surrounded as surely as any wilderness by clouds, sky, and stars. They are sparsely populated by beautiful, unsung, eccentric-seeming people who have spent decades studying the secret lives of warblers or dragonflies or nocturnal moths or mushrooms. They are our homes, our habitats, our ecosystems.

The title Crow Planet has two intertwined meanings. First, it refers to an earth upon which native biodiversity is gravely threatened, where in too many places the rich variety of species is being noticeably replaced by a few prominent, dominant, successful species (such as crows). At the same time, Crow Planet alludes to the fact that no matter where we dwell, or how, our lives are implicated in, and informed by, all of wilder life through the insistent presence of native wild creatures (such as crows).

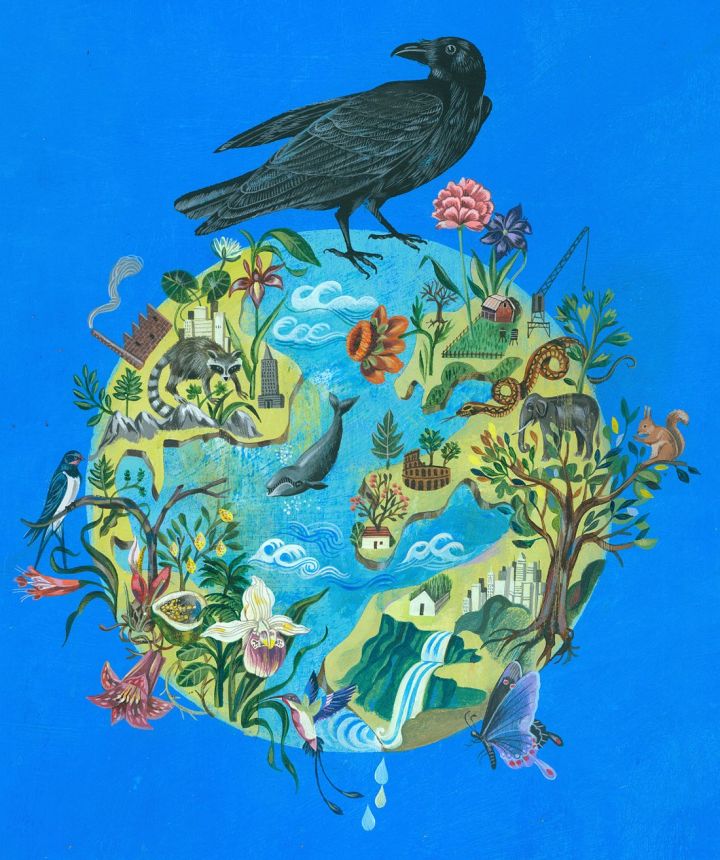

Laced with posing quotes from famous writers and opening with beautiful illustrations by Daniel Cautrell, Lyanda Haupt sections Crow Planet into ten chapters, each relaying a particular aspect of crow life while simultaneously probing the deeper crossways of humans and nature. Throughout, Haupt herself seems to be going on a journey, emerging from the cocoon of a “post-hippie Earth-firster, tree-sitting, ecofeminist, radical birdwatcher, Earth Mother” into a—simply put—hopeful academic. The narrative’s a bit weighed in humble complaints and brags, Haupt clearly unable to fully shake away the emotional attachment of believing herself to be distinctive and, for a lack of a more accurate word coming to mind, special. That said, Haupt is a genuinely interesting human being, with insightful things to say and a wide, balanced range of knowledge. Without ado I can say I enjoyed Lyanda Lynn Haupt, as a teacher, as an eccentric (self-proclaimed) and as a person. Poetic, enchanted by the world around her, sensitive, and earnest in her craft, Haupt has a tender touch and a rounded way of looking at things.

And the crows. Oh yes, we can’t forget about them. Being probably the reason most passersby will pick up Haupt’s book, Crow Planet delivers with a fabulous banquet of knowledge about our chatty, trash-picking, wind-surfing neighbors. Information both nomothetic and anecdotal, unless already a crow expert, a reader is certain to learn a thing or two about corvids. From social behaviors to anatomy, from mating and parental rituals to flight dynamics, Lyanda Haupt’s book is sure to cover most questions a crow lover would like answered. Additionally, on more than one occasion, Haupt expands her expertise on birds to reveal herself to be a fine intellect of other subjects, such as history and botany. Yet perhaps most engaging, and most enduring, is Haupt’s helpfulness in guiding others to become explorers of their own backyards. Crow Planet does more than lecture; it provides a prosaic toolkit for the how-tos of looking and taking notes. Anyone can be a researcher of nature, Haupt assures, for there’s simply so much to see, that 7 billion people all scratching at once in their journals wouldn’t be enough to jot it all down. In Haupt’s writing, one thing is clear: that the world is vast and changing all the time, and to catch a bit of its wisdom one must be willing to sit patiently for a time, and watch, and listen, and diligently take some notes.

I see more gulls than crows nowadays, having moved closer to the sea and away from the cemetery. I enjoy the pulsing calls of the seabirds in the morning, but at times, I find myself wistful for the mad croaks of crows permeating the quiet of the day. Last spring, a crow pair had made a nest atop my new apartment building, and each night of angry gusts the wind would send bits of bric-a-brac all over the community deck, shiny coins and coat buttons and yarn all over the tables and chairs. The urban wilderness is messy, and crowded, all of us trying to find where we fit in within the ceaseless turning wheel of existence and time, but I maintain that what the crow thinks of me is similar to what I think of the crow: another occupant, to which I should respect and abide by. Occasionally, we will pique each others interest, and perhaps form a friendship; maybe we will meet each other’s eyes, and encounter a more profound understanding.

But ultimately, as Lyanda Haupt reminds, we are together in all of this. This planet is our home, and increasingly, we as humans need to be more mindful of taking care of it. We all take up space, which makes it all the more imperative to make sure we make room for others. Crow Planet: Essential Wisdom from the Urban Wilderness is a dreamy, musing guide on how we might go about creating space, and how we might go about refashioning our human world into a scape that is more heedful, more respectful, and more caring to our flora and fauna neighbors. Including crows.

Four out of Five stars for Crow Planet: Essential Wisdom from the Urban Wilderness.

And now, a poem.

Crow

Dear crow, with your cold, shined wing. I never see

the goldfinches, the robins, the chickadees, the stellar jays,

only you. Only you, with your cackles, your

folk dances, invisible hurdles you are maneuvering,

sudden launches, lithe, and pillow fine landings, your hands

gripping the spider web of cables that stretch from Snohomish

to Tukwila, you are everywhere, all at once

one hundred versions of you leap into the air

as a black wild fire, a storm of onyx, an ebony deluge

that is seizing the peaceful blue day and sending death

a marching across my mind. I see my loved ones, long passed,

in the obsidian cloud swirling, harking laughs

echoing across Aurora Avenue, slick eyes wide, beaks

stabbing at the bone housing my heart set on the lonely island

of this mortal life. Yes, yes I know, that one day,

I will be a morsel, dust of the earth. You’ve instructed.

Crow, I have dreams of you, inside my bedroom,

speaking in a human voice. You are always uncommonly kind.

“Crow” by Renwick Berchild, first published in March, 2017.

The cover image is of Vincent van Gogh’s “Wheatfield with Crows” painted July 1890. Van Gogh died on July 29th that year, so it is believed to be the last piece he ever painted, though it is uncertain among historians, as no clear records exist. Image provided by Wikipedia – Thank You.

“It was a pleasant, cloudless Brisbane day. The sun beamed cheerfully across the balconies of the vacant flats opposite. I slid the balcony doors aside, and felt the warm breeze play gently on my face. What a lovely day. By now Frank, Frank who was dead, would have reached the gym, probably flirting with the receptionist on his way to the locker room. If he hadn’t been dead, that is.

“It was a pleasant, cloudless Brisbane day. The sun beamed cheerfully across the balconies of the vacant flats opposite. I slid the balcony doors aside, and felt the warm breeze play gently on my face. What a lovely day. By now Frank, Frank who was dead, would have reached the gym, probably flirting with the receptionist on his way to the locker room. If he hadn’t been dead, that is.

Although the analysis of language is the focus of this book, it is really a work of psychology. Whereas linguists are primarily interested in language for its own sake, I’m interested in what people’s words say about their psychological states. Words, then, can be thought of as powerful tools to excavate people’s thoughts, feelings, motivations, and connections with others. With advancements in computer technologies, this approach is informing a wide range of scholars across many disciplines–linguists, sociolinguistics, English scholars, anthropological linguists, neuroscientists, psycholinguists, developmentalists, computer scientists, computational linguists, and others. Some of the most innovative work is now coming from collaborations between academics of all stripes and companies such as Google.

Although the analysis of language is the focus of this book, it is really a work of psychology. Whereas linguists are primarily interested in language for its own sake, I’m interested in what people’s words say about their psychological states. Words, then, can be thought of as powerful tools to excavate people’s thoughts, feelings, motivations, and connections with others. With advancements in computer technologies, this approach is informing a wide range of scholars across many disciplines–linguists, sociolinguistics, English scholars, anthropological linguists, neuroscientists, psycholinguists, developmentalists, computer scientists, computational linguists, and others. Some of the most innovative work is now coming from collaborations between academics of all stripes and companies such as Google.

The long room we sisters shared had four round windows of colored glass: soft violet, blood-red, midnight-blue, beech-green. Beyond them the full moon was sailing up into the night sky. I put Gogu on a shelf to watch as I took off my working dress and put on my dancing gown, a green one that my frog was particularly fond of. Paula was calmly lighting our small lanterns, to be ready for the journey. […]

The long room we sisters shared had four round windows of colored glass: soft violet, blood-red, midnight-blue, beech-green. Beyond them the full moon was sailing up into the night sky. I put Gogu on a shelf to watch as I took off my working dress and put on my dancing gown, a green one that my frog was particularly fond of. Paula was calmly lighting our small lanterns, to be ready for the journey. […]

I do not know why I come to the window— / white curtains framed by a white wall. / The first breath of morning moves them. / They do not hesitate. / If rain dampens the leaden sill, / they shiver in the washed air, / waver when an animal heat crawls / hour by hour across the yard, / tremble when another summer / crumbles to dust. Some days / they refuse to move as if they hear / crows scolding them from the trees. / Soft as an owl’s downy breast, they allow / the light of dawn into the house / to nest on the floor by the bed. / Behind them, everything fades. / I do not know why I come to the window.

I do not know why I come to the window— / white curtains framed by a white wall. / The first breath of morning moves them. / They do not hesitate. / If rain dampens the leaden sill, / they shiver in the washed air, / waver when an animal heat crawls / hour by hour across the yard, / tremble when another summer / crumbles to dust. Some days / they refuse to move as if they hear / crows scolding them from the trees. / Soft as an owl’s downy breast, they allow / the light of dawn into the house / to nest on the floor by the bed. / Behind them, everything fades. / I do not know why I come to the window.

One after another, the characteristic features of time have proved to be approximations, mistakes determined by our perspective, just like the flatness of the Earth or the revolving of the sun. The growth of our knowledge has led to a slow disintegration of our notion of time. What we call “time” is a complex collection of structures, of layers. Under increasing scrutiny, in ever greater depth, time has lost layers one after another, piece by piece. […]

One after another, the characteristic features of time have proved to be approximations, mistakes determined by our perspective, just like the flatness of the Earth or the revolving of the sun. The growth of our knowledge has led to a slow disintegration of our notion of time. What we call “time” is a complex collection of structures, of layers. Under increasing scrutiny, in ever greater depth, time has lost layers one after another, piece by piece. […]

The real x factor here is not the vagaries of climate science, but the complexity of human psychology. At what point will we take dramatic action to cut CO₂ pollution? Will we spend billions on adaptive infrastructure to prepare cities for rising waters—or will we do nothing until it is too late? Will we welcome people who flee submerged coastlines and sinking islands—or will we imprison them? No one knows how our economic and political system will deal with these challenges. The simple truth is, human beings have become a geological force on the planet, with a power to reshape the boundaries of the world in ways we didn’t intend and don’t entirely understand. Everyday, little by little, the water is rising, washing away beaches, eroding coastlines, pushing into homes and shops and places of worship. As our world floods, it is likely to cause immense suffering and devastation. It is also likely to bring people together and inspire creativity and camaraderie in ways that no one can foresee. Either way, the water is coming. As Hal Wanless, a geologist at the University of Miami, told me in his deep Old Testament voice as we drove toward the beach one day, “If you’re not building a boat, then you don’t understand what’s happening here.”

The real x factor here is not the vagaries of climate science, but the complexity of human psychology. At what point will we take dramatic action to cut CO₂ pollution? Will we spend billions on adaptive infrastructure to prepare cities for rising waters—or will we do nothing until it is too late? Will we welcome people who flee submerged coastlines and sinking islands—or will we imprison them? No one knows how our economic and political system will deal with these challenges. The simple truth is, human beings have become a geological force on the planet, with a power to reshape the boundaries of the world in ways we didn’t intend and don’t entirely understand. Everyday, little by little, the water is rising, washing away beaches, eroding coastlines, pushing into homes and shops and places of worship. As our world floods, it is likely to cause immense suffering and devastation. It is also likely to bring people together and inspire creativity and camaraderie in ways that no one can foresee. Either way, the water is coming. As Hal Wanless, a geologist at the University of Miami, told me in his deep Old Testament voice as we drove toward the beach one day, “If you’re not building a boat, then you don’t understand what’s happening here.”

“[…]traumatized people become stuck, stopped in their growth because they can’t integrate new experiences into their lives.[…] Being traumatized means continuing to organize your life as if the trauma were still going on—unchanged and immutable—as every new encounter or event is contaminated by the past.’

“[…]traumatized people become stuck, stopped in their growth because they can’t integrate new experiences into their lives.[…] Being traumatized means continuing to organize your life as if the trauma were still going on—unchanged and immutable—as every new encounter or event is contaminated by the past.’